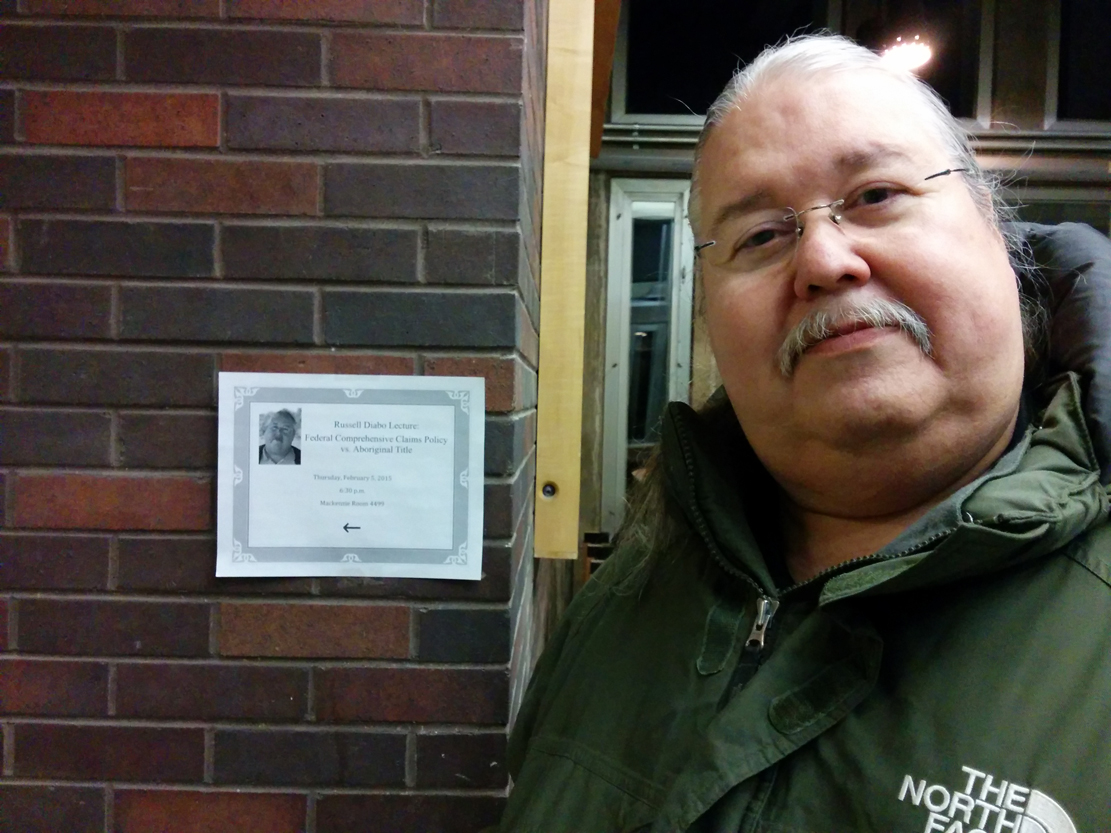

Interview with policy analyst and advisor with the Algonquin Nation Secretariat, Russell Diabo, on the ongoing Algonquin land claim for Eastern Ontario. Audio interview aired last year on CKCU 93.1FM OPIRG Roots Radio (mp3 file here) with transcript below – interviewed by Greg Macdougall.

Excerpts of this interview included as part of a printable 2-page pdf handout about the land claim.

My name is Russell Diabo, I’m a member of the Mohawk Nation of Kahnawake, but for the past I guess 30 years now I’ve been working with different Algonquin communities, including the Algonquins of Barriere Lake, and I’m an adivsor with the tribal council called the Algonquin Nation Secretariat and I’m also an advisor with the Wolf Lake Algonquin First Nation.

Q:

Okay, thanks. And if you could just summarize, so about the eastern Ontario Algonquin land claim, just summarize what’s happening and where that’s at now.

A:

In the mid-1980s, Pikwakanagan, also known as Golden Lake, submitted a land claim to a large part of eastern Ontario that basically runs from Hawkesbury to North Bay. They did that without the agreement of the other Algonquin First Nations, and that claim was being treated as a comprehensive [land] claim, although the government says that the land was extinguished through the Williams Treaty in the 1920s.

Nevertheless, in 1991, the Ontario government accepted the Golden Lake claim for negotiation, and in 1992 the federal government accepted it for negotiation. And after that, they created this policy fiction called the ‘Algonquins of Ontario’, because the Algonquin Nation was never split – the provinces were carved out of the Algonquin Nation territory, which pre-existed Ontario and Quebec.

Now they’re saying there’s this Algonquins of Ontario that have this land claim. they’ve excluded the other communities who are headquartered on the Quebec side, and the issue is about the interests that the Algonquins on the Quebec side have in Ontario.

But also Golden Lake has lands in Quebec as well, traditionally that they’re connected to. And for many years they were also considered ‘Quebec Indians’, Golden Lake, because they came from Lake of Two Mountains, or Oka, and for many years there was a fund for the Indians of Quebec and that paid for a lot of the services and that, that Golden Lake were getting. So it’s ironic that they’re now calling them the Algonquins of Ontario when they were originally considered Quebec Indians.

Q:

And Algonquins of Ontario is not only Golden Lake, they’ve brought in more people as well?

A:

Yes, so Pikwakanagan, looking at expanding – as I understand it – the land and cash portions of a final settlement, wanted to expand the numbers, so they asked for anybody they could trace their ancestry to a number of petitions that were made by Algonquins in the 1800s. So any individual that was on that list, if they could trace some connection to them genealogically, then they could be part of the negotiations.

But our understanding is they’ve gone on to create a registration system in isolation from the other Algonquin communities, and that Algonquin registry system that they’ve set up under the so-called Algonquins of Ontario process, will establish who beneficiaries are under any kind of final settlement, and will have an impact on other Algonquins. So, other Algonquins haven’t had any say in this registration system, it’s something that the governments and Golden Lake have created.

Q:

And, so you’ve been saying this has been going on a while now, like over two decades now.

A:

Well like I said, it was in 1991 that Ontario agreed to negotiate, and Canada in 1992, so it’s been going on since 1992.

Q:

And through this they’ve … I know you’re very big into explaining the whole comprehensive [land] claims process with Canada, but they [the Algonquins of Ontario] have been borrowing money …

A:

So far they’ve borrowed 18 and a half million dollars and counting, because they’re nowhere near settling. They’re not even at the agreement-in-principle stage, they have something called a draft preliminary agreement-in-principle that they’re supposed to have a referendum on – which is unusual, usually in these negotiations, they don’t usually have a referendum until maybe an agreement-in-principle stage or a final agreement, certainly a final agreement. But this is called a preliminary draft agreement-in-principle, so it’s pretty unusual, even that being so tentative.

Q:

Okay. Is that where it’s talking about 300 million dollars and 1-point-something percent of the land?

A:

Yes, there’s a number of … the highlights of the Algonquins of Ontario preliminary draft agreement-in-principle says that there will be a fund if they reach a final agreement. I mean that’s the whole point, is that this is like, it sets out the principles, and the details have to be worked out in the final agreement. So the 300 million dollar fund, and they’re doing a land selection process, trying to pick the best lands in eastern Ontario, but they’re picking lands that other Algonquin First Nations have title and rights to as well. And many of these people, who have been registered as Algonquins – like six to eight thousand of them – many of them will likely not be able to meet the legal standard of being Aboriginal title holders, yet in this process they get to extinguish title, through the process.

Q:

And when you mention extinguishing title, you were mentioning the Supreme Court basically said there’s two ways: you can either negotiate, and then through negotiation you’re extinguishing the rights …

A:

In June 2014 the Supreme Court of Canada issued the Tsilhqot’in decision, otherwise known as the William decision. In there they reaffirmed the legal principles in the previous Delgamuukw decision of the Supreme Court, where they said Aboriginal title means the right to determine the purposes to which the land would be used – it’s a property right, there’s an economic component to it – so this Tsilhqot’in case basically reaffirmed all of that, including the duty to consult and accommodate at the assertion stage, because they’re saying there’s two stages of Aboriginal title: one is groups who are asserting Aboriginal title, which is most of the groups, including the Algonquin First Nations I work with; and in order to establish Aboriginal title, the Supreme Court in the Tsilhqot’in case said you either have to go seek a court declaration, which means you have to have basically millions of dollars worth of research and money to sustain the court challenge, and … or you negotiate, and the only way to negotiate is through the existing comprehensive claims policy of the federal government, which requires extinguishment of Aboriginal title, not recognition – plus you have to borrow money, there’s a whole bunch of problems with it: third party interests take more priority, they want a release from past infringements or alienations of land, they don’t compensate for that, but they want a sign-off by the First Nations, so there’s a whole bunch of problems with that policy.

Q:

And you were talking about the Algonquin communities you’re working with, are working on asserting title and rights.

A:

They’re at the stage of asserting title and rights, and in January 2013 they submitted what’s called a Statement of Asserted Rights and Title, for the three communities, and it wasn’t a comprehensive claim or Aboriginal title claim just yet/ It was presented to the crown governments, Ontario Quebec and Canada, to push for a formal consultation protocol, like the Haida decision says, that you have to give notice to the crown governments on the nature of the rights you’re asserting and where you’re asserting them. So they basically gave a summary of evidence and a map to the governments and said ‘ok we’re asserting title and rights over this territory’. And the governments ignored that, and they’ve continued, where there’s overlap with the Algonquins of Ontario, they’ve continued to negotiate with them and ignore the other Algonquin First Nations, certainly the three that I work with.

Q:

What three are those?

A:

That would be the Wolf Lake First Nation, Timiskaming First Nation, and the Eagle Village First Nation.

Q:

So where does that go, if the governments are ignoring this assertion on land that’s being negotiated separately?

A:

Well, they have the court decision to deal with, so they either have to consider legal action or political action or both. Those are the options they have in front of them. Right now they’re pushing the governments for consultation, formal consultation processes, to consult and accommodate on any development of lands or natural resources within their Aboriginal title territories. So that’s what they’re looking for right now.

So they’re engaging Quebec, they just signed a memorandum of understanding between the three communities on how they’re going to deal with consultations from the Crown governments, and they’re pushing Quebec for an agreement, an MOU – memorandum of understanding, and consultation – and they want one from Ontario as well, and one from Canada in areas where federal things like the Energy East project, the pipeline going through their territories. And also there’s dams up there. And then there’s also things like environmental assessments of a proposed rare earth mine, other things that have some federal areas of jurisdiction in there too.

~~~~ ‘break’ ~~~~

Q:

And the other community you mentioned was Barriere Lake, and they’ve taken a different approach to land title or rights or …

A:

Well the Algonquins of Barriere Lake are part of the Algonquin Nation Secretariat, the tribal council I work with, and they entered into a series of agreements with Canada and Quebec that were outside of the claims process. The first one was the 1991 Trilateral Agreement, which basically is a resource management agreement that agreed that there’d be an integrated resource management plan prepared for forests and wildlife over ten thousand square kilometres of their territory, and in 1998 they signed another agreement with Quebec, a Bilateral Agreement, on how they would implement the first agreement. But in there, Quebec also agreed to negotiate co-management revenue sharing, and now Quebec is telling them that they’ll negotiate everything except for revenue sharing – so in effect they want to breach that part of the agreement, because they did mandate John Ciaccia to negotiate for them, he was a former cabinet minister of Quebec, and he recommended that Barriere Lake should get a million and a half a year in annual contributions for the exploitation of resources off their Trilateral Agreement territory. But Quebec doesn’t seem to want to include that in the negotiations, according to the correspondence they’ve received from the government.

Q:

And my understanding, just to be clear, is that that agreement wasn’t giving up any rights.

A:

No, that agreement had nothing to do with giving up title and rights. In fact, it was based on the Bruntland report – in 1987 there was a United Nations [World Commission] report on environment and development, and there were a number of recommendations in there that Barriere Lake took up. One was it said that Indigenous people should have a decisive voice in resource management decisions that affect them, the other one was this concept of sustainable development, of making sure that resource development occurs in a sustainable way, and the other one was conservation strategies – they wanted a conservation strategy applied to their territory. In the course of negotiating with the government of Quebec, and Canada, that turned in to the development of an integrated resource management plan based on the principles of conservation and sustainable development.

So, that was part of the negotiation process, but it was more based on promoting sustainable development of the territory and putting some controls over forestry instead of having clear-cuts, and they’re also affected by ongoing flooding from reservoirs, the Cabonga and Dozois reservoirs, which are part of the Hydro Quebec system, where Quebec’s making money off of that. Basically, there’s about a hundred million a year in resource development coming off Barriere Lake’s territory, and they don’t get one cent, so that’s why they’re wanting revenue sharing. And they want to have co-management, to have a say in how logging’s done, and how wildlife management occurs in their territory.

There’s been a small group in the community that’s been very vocal right from the beginning, that haven’t agreed with that – they wanted everything shut down. But the community talked about that at the beginning, and they realized that they… there’s many Quebecers that get jobs up there from forestry, so they talked about three options: no logging, which they knew they’d be fighting the towns of Maniwaki and Mont-Laurier and Val d’Or where these workers come from and the mills are; the second one was do nothing, just let Quebec pass laws and log their territory; and the third option they talked about was controlled logging, and that’s what they chose and that’s what became the Trilateral Agreement, was a way to control logging up there, to protect the Algonquin sites, cultural sites, and environmental areas.

But the government has not liked that agreement after signing it, in fact Canada pulled out of it in 2001 – Robert Nault was the minister [of INAC, now AANDC] then under Jean Chretien, they breached the agreement by walking away. So in 2002, Quebec picked up the process and covered the costs that the federal government was supposed to cover, and that process continued until about 2006, when John Ciaccia, the Quebec representative, and Clifford Lincoln, the Algonquin representative, issued a report of joint recommendations that included co-management and revenue sharing.

The government sat on that, those recommendations of the report, and instead Canada and Quebec started manipulating the internal affairs of the community, the governance, promoting factions, and they were trying to kill off those agreements. And for a while the community conflict over leadership distracted them from dealing with making sure these agreements were being honoured. But they came together about four years ago – they were forced from a customary [governance] system into an Indian Act electoral system, so they’ve been electing their chief and council, and it’s only a small group that remains opposed to the chief and council, but most of the community are behind them, and they’re the ones who are trying to get these agreements honoured now. And so they are furthering negotiations with Quebec, but they want revenue sharing included, as was originally intended.

And Canada is still not at the table, because Canada wants them to go into the comprehensive claims policy, that’s what they’re trying to push them into. So that’s why they never liked the Trilateral Agreement, because it wasn’t under the comprehensive claims policy – it doesn’t lead to extinguishment of title; if anything, it reinforces title, because them having a management role in resource management and getting revenue sharing, that’s all reinforcing Algonquin rights and jurisdiction over resource management.

Q:

So, with these different approaches, where do you see things going, and what do you think people can take away from understanding this issue … and what’s important for people living in this area to know about this?

A:

Well what the research has shown from the three Algonquin communities – actually the four, including Barriere Lake – is that, for the Algonquin Nation, Aboriginal title resides at the community level, not the nation level. And the Algonquins at the nation level came together, especially in the summer and that, but the Algonquin First Nations are made up of the modern Indian Act bands, and traditionally those are the extended families that form those modern bands. But there are historic bands that they are descended from, or that they succeed.

So, the whole issue about who’s the legitimate representatives is important: there are duly-elected chiefs of these 10 Algonquin communities, including Golden Lake in Ontario and nine in Quebec, and there’s these other people coming up claiming to be Algonquin chiefs but there’s no evidence to show that they have any of those titles/ or that they’re even connected to a recognized community. So these issues have to be made clear to the public, because there’s so many people coming forward claiming to be representatives of the Algonquin Nation – and groups, who aren’t. So that’s one of the first things that needs to be cleared up.

Once you know who to talk to, who has the legitimacy, that is going to be important, but the Algonquins, the Algonquin Nation within itself, they have to have discussions about what they’re going to do. Because even within the Algonquin Nation there’s two tribal councils on the Quebec side, and then you’ve got this Golden Lake with these nine satellite groups who are not status, on the Ontario side. So there’s going to be a lot of issues to sort out within the Algonquin Nation. And so I can understand why it’s confusing for the public.

Q:

And just a final reminder that the Ottawa River, [as] the Quebec/Ontario boundary, is not something that was traditional …

A:

No, the Algonquin Nation pre-existed the creation of the provinces of Ontario and Quebec – they carved the provinces out of the Algonquin Nation territory. Which is why I say the ‘Algonquins of Ontario’ is a policy fiction that’s been created for the governments, for negotiation purposes. Because it’s basically a land grab by the Crown governments, because they want to extinguish title to eastern Ontario, and especially the National Capital Region, where Parliament Hill sits, the Governor General’s residence, the Prime Minister’s residence – the whole city of Ottawa is sitting on unceded Algonquin territory, so they want to make sure that it gets ceded.

And that’s what they’ve been pushing all the Algonquins into, is trying to get them into the comprehensive claims process. So they’re trying to use the Algonquins of Ontario claim as a precedent against the other Algonquins – a very low precedent, because it’s going to set a low standard if this agreement goes forward.

Q:

Thank you.

================================

================================

For more audio/podcasting from EquitableEducation.ca:

- Audio posts on this site: www.EquitableEducation.ca/category/audio

- RSS feed for subscribing: https://EquitableEducation.ca/?cat=audio&feed=rss2

Interdependent media & in-person learning opportunities for those who are inspired to be part of movements for social justice.

Interdependent media & in-person learning opportunities for those who are inspired to be part of movements for social justice.

Chi-Miigwetch.