After leading two walking tours of the Sacred Site at ‘Chaudière Falls’ in Ottawa, it was suggested – and I thought a good idea – to put the information together online: thus this post. It is longer than originally intended, but that is because it is a complex and detailed situation.

This is estimated as a 23-minute read (also with embedded audios and many reference links) – but there’s a clickable Table of Contents below if you’d like to jump to a particular section / read it in parts.

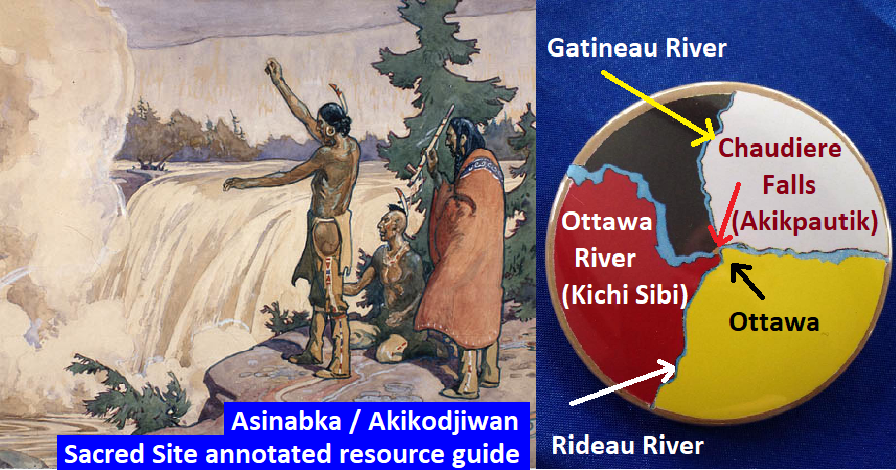

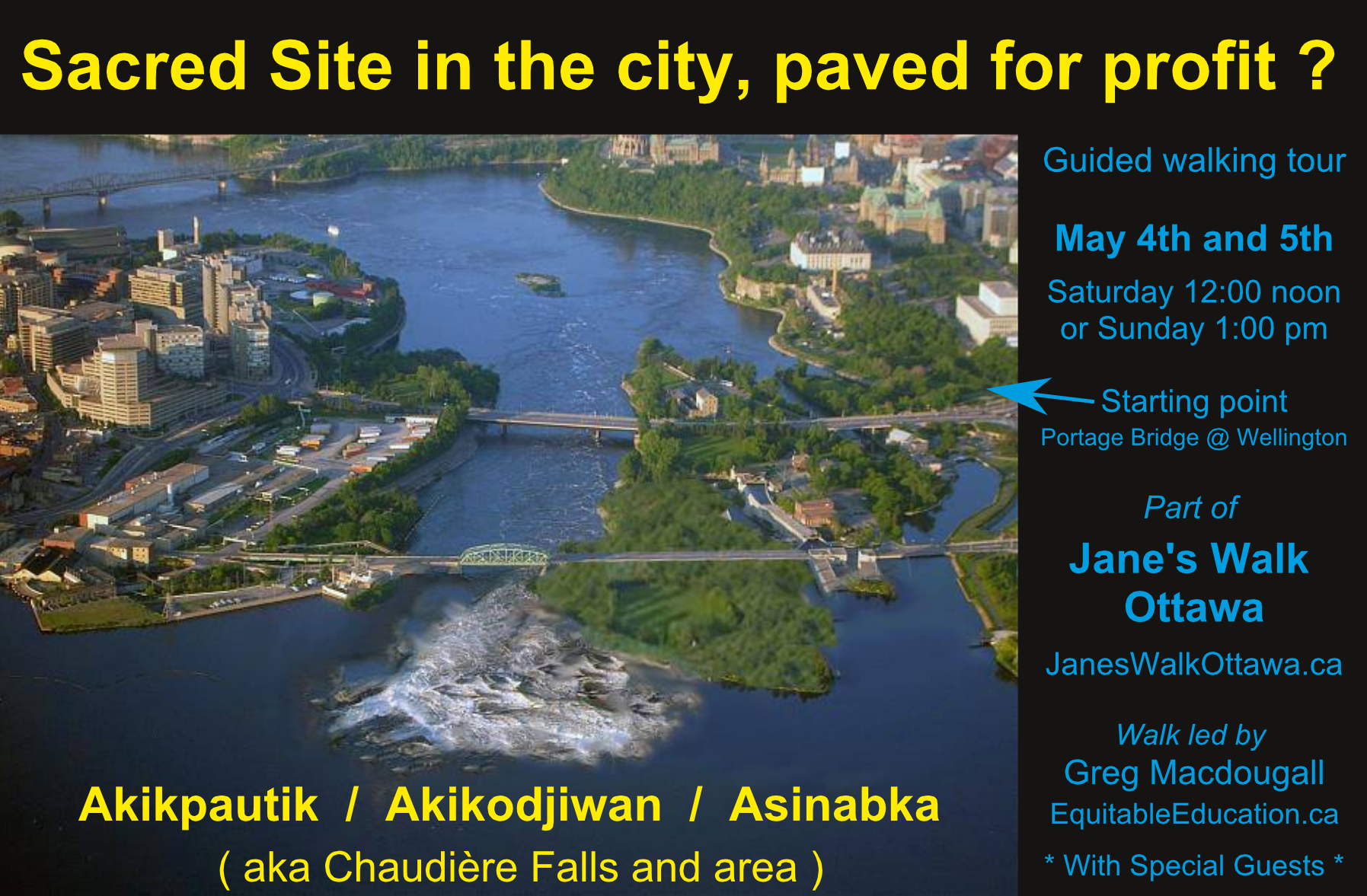

The walks were part of Jane’s Walk the first weekend in May, “a festival of free neighbourhood walking tours that help put people in touch with their city, the things that happen around them, the built environment, the natural environment, and especially with each other… [It] is a pedestrian-focused event that improves urban literacy by offering insights into local history, planning, design, and civic engagement.” It is named after “urbanist and activist” Jane Jacobs.

The two-fold purpose for this walking tour was:

- To provide context and details about this Sacred Site, specifically with regards to the past five years since a planned development (‘Zibi’) was announced.

- To honour the work and life of Harry St. Denis, the former chief of Wolf Lake Algonquin FN, who passed away November 2018 and had been one of the leaders in working to protect the site.

Chi Miigwetch to the many family members of Harry who came to participate in the walk from Wolf Lake FN and also Kipawa FN. Also the Barriere Lake FN community members who traveled a similar distance to participate. Chi Miigwetch also specifically to the guest speakers for the walk: Peter Di Gangi, Norman Matchewan, and Rosanne Van Schie on the Saturday; and Warren Papatie on the Sunday. And also many thanks to the Jane’s Walk Ottawa-Gatineau organizers and marshals who helped with these two walks as well as the more than 60 other walks over the weekend. And thanks to all those who took the time to come and be part of this particular walk!

The primary points to do with the development, points seemingly contentious to some, are that: the area is an historical, traditional Sacred Site; the land is unceded Algonquin territory; there is not Free, Prior, and Informed Consent from the Algonquin Nation as a whole for the developments(*) at the site; the different levels of governments are violating the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, as well as Canadian constitutional law, in allowing the development to proceed; and the development has created harmful divisions within the Algonquin Nation and the individual communities.

(*developments plural, both the condo/commercial development and the new hydro facility at the dam)

The sections below are roughly in order as presented at the walk – but with a special section at the bottom featuring Chief Harry St. Denis. They are:

- Intro notes

- Route of the guided walk

- Handouts – pamphlets

- Algonquin names for the Sacred Site

- History of the area

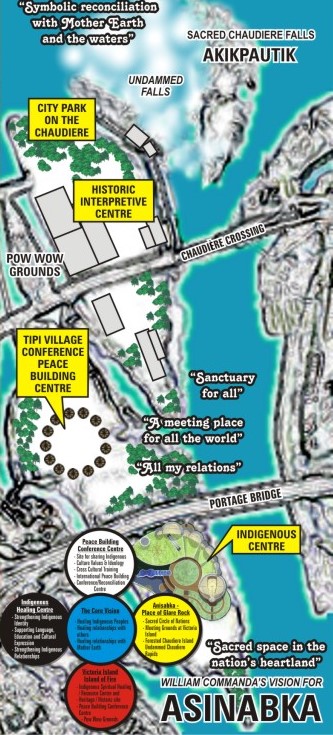

- The Asinabka Vision

- The planned development

- Protecting the Sacred Site

- The Eastern Ontario Algonquin Land Claim

- The Hydro Dam and Public Park

- The advocacy of Chief Harry St. Denis – and tribute

If you think the content here is worthy of sharing, please do!

Send an email or post on social media, but please be sure to add a sentence or two about what you feel is important, for the people who will be wondering whether they should click on the link.

Also if you have any constructive feedback, please leave a comment or email me. I may do a revision in a while; aside from a few paragraphs, there’s been no editorial support on this (>5000 words) work. If there are significant changes made, they’ll be noted here.

*UPDATES

June 17th: Have added Land Registry record upload, all historical records astransferred to microfilm in 1998; also notice of the new Chief Harry St. Denis Scholarship for Indigenous Environmental Students.

All the original content here © Greg Macdougall / EquitableEducation, 2019 (to protect against misuse). No re-use without written permission, except for short quotations that are credited / accompanied with a link to this webpost.

INTRODUCTORY NOTES:

The acknowledgement of unceded Algonquin Anishinaabe territory was less a separate formal thing at the start of the walk and more included throughout the walk itself.

For ideas around allyship and solidarity work etc, in the context of a non-Algonquin person leading this walk, please see the book Taking Sides: Revolutionary Solidarity and the Poverty of Liberalism, a collection of essays, edited by Cindy Milstein and published by AK Press. Some of the essays also have versions published online, for example “Ain’t No PC Gonna Fix It Baby” (some highlights here).

What is contained here are mostly items that are documented and accessible online (links to text, images, audio or video). Much of it is not first-hand knowledge. It’s also important to note that a lot of knowledge is held in the communities, by knowledge-keepers, and in the oral tradition – and that is beyond the scope of this resource guide.

Also to note is that if someone(s) else were to choose what is or isn’t relevant for this kind of summary/ resource guide, their collection might highlight different things, and that highlights how relevance is based in part on perspective. However, this is an attempt at a cohesive and comprehensive overview of the main issues to do with the proposed development.

WALKING TOUR ROUTE:

The first few topics here – the names for the site, it’s history, and the Asinabka Vision led by William Commanda – were all presented at the starting point of the walk. This was at the Ottawa end of the Portage Bridge, where it meets Wellington St, at the ‘Gather-Ring‘ art installation.

We then crossed the street to walk along the sidewalk of the Parkway (what Wellington turns into, headed west). The development comes into view at about the location of the Mill Street Pub sign, and from there we walked along the water-side walking path towards the War Museum until reaching the Chaudiere Bridge, aka Booth St on the Ontario side.

The high water levels (see video from Hydro Ottawa and comparison of water amounts with Niagara Falls) had led the federal government to close the metal Union / Dominion bridge that is in the middle of the overall Chaudiere Bridge, but we were able to coordinate with their contracted security on both walks to (after our official 1.5hr tour time) access the public park / viewing platform that are directly adjacent on the south of the dam/waterfalls.

(*To access the park/ platform at the falls: Take a west turn at the traffic lights immediately south of the metal bridge, “4 Booth St” on the map. The platform is a turn after the first buildings; the park is ‘walk as far as you can’ to the fenced bridge and over, almost directly to the side of the dam.)

Parliament is at top centre; Museum of History/’Hull Landing’ top left before the bridge.

HANDOUTS:

The 3 handouts provided for walk participants are available as PDF files at the Printable Items tab above.

They were

- The 2014 article after the rezoning decision, and the 2015 call to protect the Sacred Site

- The 2016 pamphlet for the Algonquin land claim.

2006 diagram via Circle Of All Nations

Created when GWC awarded Key to the City of Ottawa

NAMES OF THE SACRED SITE:

The Anishinaabemowin / Algonquin names for the Sacred Site:

- Akikpautik (aka ‘Pipe Bowl Falls’)

- Asinabka (aka ‘Place of Glare Rock’)

- Akikodjiwan (see note below)

The Akikpautik name refers specifically to the waterfalls (or, rapids is what pautik translates as). Both Asinabka, the name most know from Grandfather William Commanda’s vision for the site, and Akikodjiwan, the name included in the Algonquin chiefs’ call and resolutions of 2015, are used to refer to the full area including islands and shoreline.

Romola Thumbadoo writes:

“With respect to Algonquin terminology associated with the Chaudiere Site, Asin means rock, and in particular glare rock, bedrock, which has no covering; Asinabka is the Place of Glare Rock, associated with a primary gathering place of the ancient people of the Ottawa River Watershed, at the confluence of three important rivers and waterfalls; Akik means pail/bucket; Pautik means rapids; Akikpautik is then the pail/bucket rapids, different, for example from the Rideau Falls; Odjiwan describes water flowing through rock, and they occur in many places across Algonquin Territory; at the Chaudiere, Akikodjiwan refers to the water that flows through rock at the Akik/Pail (this referenced the two “black holes” that made sound from the womb of the earth, as it were, at the Chaudiere, and that were sealed in colonial times).” – Romola Thumbadoo was the late William Commanda’s personal assistant and biographer, and coordinator of the Circle of All Nations network he founded; she notes that he was a master linguist who spoke two versions of Algonquin, one a very ancient one and one contemporary version, and many dialects of Algonquian (the larger language family) roots, as well as both French and English.

There is also this piece, about the Akikpautik name and Indigenous place names more generally, by Dr. Lynn Gehl, Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe.

Note – Excerpt from the Lexique de la langue algonquine, by J.A. Cuoq 1886, p31:

Akikodjiwan, Saut de la Chaudière, les Chaudières, où l’eau tombe dans des bassins de pierre qui par leur forme arrondie ressemblent à des chaudières. Ce lieu porte aussi le nom de Akikendátc, “là où est la chaudière.” (1)

(1) Pour la même raison, les Iroquois nomment cet endroit “Kanatsio,” V.p.40 du Lexique de la langue iroquoise.

(English translation:)

Akikodjiwan, Rapids of the Boiler, the Boilers, where the water falls in stone basins which by their rounded shape resemble boilers. This place is also called Akikendátc, “there where the boiler is.” (1)

(1) For the same reason, the Iroquois call this place “Kanatsio,” V.p.40 of the Iroquois Language Glossary.

Also to note:

There is the name Asticou, which Samuel de Champlain included in his 1613 journal entry saying that was the Algonquin name for the site, meaning boiler – but a 2005 report by the Ottawa River Heritage Designation Committee (with writing team including William Commanda, Harry St. Denis, and Peter Di Gangi) notes in a footnote on page 22, “The word Asticou must be a misprint in the original text, because the Algonquin word for small cauldrons or boilers (plural) is Akikok. The missionary J.A. Cuoq says that the full name for the Chaudiere Falls is Akikodjiwan […]”

HISTORY:

The recent archaeological research mentioned during the walk (re: burial site at “Hull Landing” which is roughly the area where the Museum of History sits by the river shoreline) includes evidence dating back 5,000 years, and was published by Jean Luc Pilon and Randy Boswell in 2015. Summaries were published by Carleton University’s newsroom and by the Ottawa Citizen, and Boswell wrote a follow-up op-ed. Their published research is here, in order:

- New Documentary Evidence of 19th-Century Excavations of Ancient Burials at Hull Landing: New Light to Old Questions (Arch Notes 19; May-June 2014)

- An 1852 News Item and its Significance for the Ottawa-area Archaeological Record (Arch Notes 20; September-October 2015)

- Below the Falls; An Ancient Cultural Landscape in the Centre of (Canada’s National Capital Region) Gatineau (Canadian Journal of Archeaology 39; 2015)

- The Archaeological Legacy of Dr. Edward Van Cortlandt (Canadian Journal of Acheaology 39; 2015)

Peter Di Gangi spoke at the start of the Saturday walk, about the history of the area. In 2015 he gave a 78-minute talk on the History of the Ottawa River Watershed – he later wrote an article on the same topic, in relation to land title; he also gave an 8-minute talk as part of an event later in 2015 specifically focused on protecting the Sacred Site from development.

Samuel de Champlain visited the area in 1613, with recorded entries in his journal. In 2013 for the 400th anniversary, a colliquiuom entitled “Champlain in the Anishinabe Aki : History and Memory of an Encounter” was held at Carleton University, creating a legacy online digital repository (archived version) hosting “documents, photographs, images, and other materials relating not only to the history of Champlain’s encounter with this region, but also our memories of that encounter.”

The Sacred Site’s use by the lumber industry (Philemon Wright, EB Eddy, JR Booth, Bronson, etc) from the early 1800s until relatively recently, is a major part of the history of the Ottawa Valley and the cities of Ottawa and Hull, and the context of the current circumstances.

For a few months in 1974-75, the Carbide Mill building on Victoria Island served as the “Native People’s Embassy”, an occupation extending from the Native People’s Caravan that had started on the West Coast and arrived in Ottawa at the opening of the fall session of Parliament in September 1974 to a rough reception from police and security forces. Vern Harper’s book “Following the Red Path: the Native People’s Caravan 1974” (summary) is a good source to learn more, and is accessible via the Ottawa Public Library at the ‘Ottawa Room’ of the Main Branch.

Victoria Island was also the location of Chief Theresa Spence’s fast/ hunger strike in the winter of 2012 on the wave of Idle No More, and has been host to countless other Indigenous ceremonies and activities.

*Note: Victoria Island is closed to the public as of last fall, for the next 6-7 years, for environmental remediation clean-up of the historical pollution remaining from the lumber industry.

THE ASINABKA VISION LED BY WILLIAM COMMANDA:

Prelude:

- 1950 The Gréber Plan, which was the catalyst for the creation of the NCC (National Capital Commission), included re-naturalizing the Sacred Site:

“The restoration of the Chaudiere Islands to their primitive beauty and wildness, is perhaps the theme of greatest importance, from the aesthetic point of view-the theme that will appeal, not only to local citizens, but to all Canadians who take pride in their country and its institutions.” (pg.250) - The NCC develops idea of an Aboriginal Centre on Victoria Island starting in the ’70s (reference), and Douglas Cardinal began working with them on the project in the ’80s (reference, p.9).

Grandfather William Commanda, Algonquin spiritual leader, Carrier of Three Sacred Wampum Belts, and founder of Circle of All Nations, in the late 1990s began to advocate a vision for the Sacred Site, working with renowned Indigenous architect Douglas Cardinal. Born in 1913, Commanda passed away in 2011, and as he was the person to bring many people together around the vision, this has impacted its progress. Documentation of the Asinabka vision work are collected online at Asinabka.com, maintained by Romola Thumbadoo, personal assistant to Grandfather Commanda and coordinator of the Circle Of All Nations network, the network that is the background from which the Asinabka vision comes.

Key milestones and Circle of All Nations’ Asinabka documentation mentioned at the walk:

- Late ’90s/early ’00s Consultations and visits with Algonquin communities re: vision for Sacred Site

(read ‘Background’ section, first page of Elders’ Gathering report, linked on next line) - 2002 Elders Gathering (Final Report)

- 2003 Communities’ Gathering (Invitation and Vision Plans)

- 2006 Key to the City of Ottawa recipient speech

Two-page flyer version / Report also with notes about the event including Mayor’s remarks

Two paragraphs of Commanda’s speech clearly summarize the purpose and parts of the vision. - 2010 Asinabka Vision report, as supporting material for City of Ottawa decision

This is a very detailed, multi-section presentation/ report on the vision and plans. The City of Ottawa, approving a city committee’s recommendation to support a National Indigenous Centre on Victoria Island (section II of the report) at council meeting 19 November 2010. The report also includes plans for forming a Council of Algonquin Elders as well as an Operating Body to work on the development and implementation of the vision, and a description of the full vision.

Despite the recognition and honouring of his work – along with the Key to the City of Ottawa, Commanda was awarded two honourary PhD degrees, and appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada – and supportive words over many years from different government officials for the vision, the lack of eventual realisation was disappointing. There was a $50,000 grant from Heritage Canada in 2004 to work on plans and designs, and then $85 million earmarked by the NCC in 2005 as initial funding ($35m for the vision and $50m for soil decontamination/remediation), but that wasn’t ever applied and the larger government investment to support reclamation of the privately-occupied lands didn’t come through, even after Domtar wound down operations in 2007. Thumbadoo points to the 2006 sponsorship scandal, which also preceded the change in federal governing party, as a major impact on the government follow-through. Commanda’s approach of non-confrontation and attempting to have voluntary support from all involved didn’t work well with how government functions.

Note that the developers (see next section) on their website, after quoting Grandfather Commanda, state their project “will not conflict with [the Asinabka] vision, and we are entirely supportive of that idea” – in direct contradiction to much of what is linked to above.

THE CURRENT DEVELOPMENT PROJECT:

In the summer of 2013, Windmill Development Group publicly announced their planned ‘environmentally-friendly’ $1bn+ condo/commercial project (‘Les Isles’) for Chaudiere and Albert Islands and the Gatineau shoreline, with a letter of intent to purchase Domtar’s property interests there.

Two public information sessions were then held (the first in December 2013 at the Museum of Civilization/History, with maybe close to 1000 attendees, followed by a second smaller event at the War Museum). Two Algonquin – Kitigan Zibi then-Chief Gilbert Whiteduck as well as then-councilor Claudette Commanda – helped open the first event for Windmill (the two would eventually take opposing positions on the project: Commanda in support , and Whiteduck opposed).

In the summer of 2014, it was announced that a larger development company, DREAM Unlimited Inc, would be partnering with Windmill on the project.

Despite opposition, in October of 2014 the City of Ottawa rezoned the lands on the islands to allow for the development; the City of Gatineau rezoned the shoreline early the next year.

*LISTEN: Windmill’s Rodney Wilts interview, between city hearing on rezoning and full council approval

In February 2015 the developers announced a new name for the project – Zibi, the Algonquin name for river, chosen through a contest without Algonquin approval. The event to announce the name didn’t have any Algonquin guests on hand.

In May 2015, Pikwakanagan First Nation announced they would be working with and supporting the developers; in August, the Algonquins of Ontario (a corporation consisting of Pikwakanagan plus representatives of nine non-status communities, that was formed for land claim negotiations) also signed a letter of intent to support and collaborate with the developers.

Also, a four-woman (three Algonquin, one other non-Algonquin Anishinabe) advisory group was formed, named the Memengweshii Council (also see critical response as well as conflict of interest with NCC). One of the four council members is co-owner of Decontie Construction, an Algonquin company that formed a working relationship with Windmill / Zibi to emply Algonquin workers. A fifth member, also an Algonquin woman, later joined the council. They are paid (in honourariums) by the developers who say they’re considered volunteers.

‘Ground-breaking’ events were held on the Gatineau side in December 2015, and on the islands in spring 2017, an event that also included two of the formerly-opposed Algonquin communities (Long Point and Timiskaming, both of which had changes in leadership) announcing their new support of the development.

In December of 2017, an Order-In-Council by the federal government transferred approximately 1/3 of the island land for the development, crown land unceded by the Algonquin Nation, to fee-simple ownership of the developers. This transfer was carried out between different government departments (PSPC and NCC) and the developer conglomerate in April 2018, followed by the formal completion of transfer of the other lands from Domtar in May as the conditions for the 2013 agreement had been met.

In June of 2018, the City of Ottawa approved a ‘brownfield’ grant of $62 million to the developers, to provide half the amount required to clean up the soil at the site from the pollution left by the previous logging tenants (with subsidies or tax breaks from other levels of government still to be determined; the City of Gatineau is providing $11 million). This was despite the original claims of the developers, who in their earlier propaganda (including to justify their rezoning request) said that they were the only prospective project that would be able to pay the $100+ million required to clean up the site, and of Ottawa mayor Jim Watson, who in 2014 said the city wouldn’t contribute any money to the development.

Soon after, a new company (Theia) was launched to take control of the development, removing Windmill from the project. This was marked by a public relations event on site with special guest speaker Ottawa-Centre Liberal MP / Environment Minister Catherine McKenna.

In December of 2018, the first building – on the Gatineau side – was occupied by its first tenants.

In May 2019 the developers opened ‘Zibi House’ – both a sales centre and event hosting location – to the public. It is an 8-story tower built from cargo containers, with top-floor full-glass observatory section, and initial events featuring luxury-chef dinners.

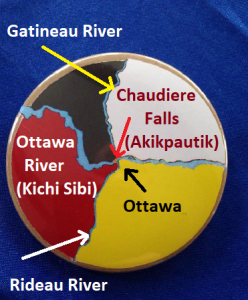

The four directions/ four colours circle customized for the Sacred Site and three rivers meeting.

PROTECTING THE SACRED SITE:

The developer’s application to the City of Ottawa for rezoning of the site to allow for the project to be built, was considered at a city committee hearing in October 2014. This was the first focal point of mobilization to protect the site from the development, with over 100 oral or written submissions against the rezoning versus three in favour. Despite this, the committee and then full city council approved the rezoning.

LISTEN: Kitigan Zibi chief Gilbert Whiteduck interviewed pre- and post- the city’s rezoning vote

Click here for his unheeded letter to the City asking for discussions before approval of the rezoning.

The formation of a group to protect the site, named Free The Falls – or more fully, Freeing Chaudière Falls and Its Islands – began soon after the rezoning, with one of its focuses to support an appeal of the city’s decision to the OMB (Ontario Municipal Board).

Six individuals officially appealed the decision to the OMB: Douglas Cardinal, Lindsay Lambert, Richard Jackman, Romola Trebilcock-Thumbadoo, Dan Gagne, and Larry McDermott. There was a 30-day window after the city’s rezoning decision, to begin appealing. The appeal was eventually judged unsuccessful (see Findings section, pg14+) in November 2015 by the OMB without even the opportunity for a full hearing. Four of the five appealed the OMB’s decision to the Ontario Divisional Court (ultimately also unsuccessful, also without opportunity for a full hearing, in March 2016) while Lambert submitted an appeal to the Office of the Ombudsman of Ontario.

* Extensive documentation of the OMB and Ontario Divisional Court appeals, is accessible online via a sub-page on Asinabka.com

The lawyer representing Douglas Cardinal, Michael Swinwood – who some of the Algonquin chiefs didn’t want involved in this issue, but to no avail – has also made other legal challenges to the development:

- April 2015, on behalf of Stacy Amikwabi, to protect multiple sacred sites.

This case was dismissed/withdrawn on the first day in court, July 2015. - March 2016, on behalf of a group of grandmothers from Pikwakanagan, challenging the land claim.

This was first filed in Federal court, later put on hold and refiled in Ontario Superior Court Spring 2017 (see official court filing). This case includes specific section on the Sacred Site. It is against the Pikwakanagan Chief and Council, the Algonquins of Ontario, and the federal government. It is still before the courts. - February 2018, on behalf of the grandmothers as well as Albert Dumont of Kitigan Zibi.

This case specifically challenges the December 2017 Order-In-Council transfer of crown land to the developers; it has been put on hold by request of the applicants since July 2018 and is scheduled to resume November 2019 (see case timeline).

In August 2015, four of the status Algonquin communities (Timiskaming, Wolf Lake, Barriere Lake, and Eagle Village/Kipawa aka Kebaowek) passed resolutions to protect the Sacred Site, and notified the different levels of government. A fifth (Long Point) separately sent the OMB a letter with their position against the sale and development of the islands. In October 2015, the four Algonquin chiefs put out a call for support to protect the Sacred Site from development, both Windmill’s condominiums and commercial project as well as the new Hydro Ottawa facility at the dam. In part, it read “we are actively seeking national support for our Algonquin land use vision as a step towards reconciliation with our legitimate Algonquin First Nations, which we believe is consistent with the vision of the late Kitigan Zibi Elder, William Commanda who advocated for the return of this Algonquin sacred waterfalls area.”

This was followed by more comprehensive resolutions at the regional Assembly of First Nations – Quebec & Labrador (link) and the full AFN Special Chiefs Assembly (link) that were supported by nine of the ten Algonquin chiefs (all but Pikwakanagan). The AFN-QL resolution was passed unanimously, while the AFN resolution was the object of pro-development lobbying and passed with many abstentions and four votes against. The call and the resolutions demanded that the development be stopped unless/until there was Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) from the Algonquin Nation as a whole, and that the federal government enter into discussions to return the site to Algonquin stewardship.

The government has yet to honour these resolutions, as no actions were taken to stop either the hydro development or Windmill’s project, but it did lead to a series of meetings between the NCC and all ten Algonquin communities/chiefs, beginning in 2016 and held a few times a year (Minister Carolyn Bennett publicly said she was willing to meet with them, but didn’t as far as I’m aware). The NCC frame these as consultations but at least some of the chiefs have expressed the experience(*) as lacking in consultation, and more along the lines of information sessions – hear more about this in the audio directly below with then-chief of Kitigan Zibi, Jean-Guy Whiteduck and also in the audios further below in the section featuring Chief Harry St. Denis (*note: the chiefs in the video, Verna Polson and Kirby Whiteduck, speak more about Lebreton Flats, but it is the same process/meetings that started with and are also about the Sacred Site and Zibi).

In December 2016, Kitigan Zibi launched a land title claim for a specific area from Parliament Hill west to Lebreton Flats in Ottawa, including the islands at the Sacred Site (see article from iPolitics, and court filing document). Chief Jean-Guy Whiteduck explained in October 2017 that this court action was more to force the government to meaningfully engage in negotiations and consultations, and that continuing to follow it through in court is a last resort

LISTEN: Jean-Guy Whiteduck excerpts, October 2017 discussing Hydro Ottawa and NCC ‘consultation’ processes, and the site-specific Aboriginal title claim for Parliament to Lebreton and the islands:

Alongside the chiefs’ calls to protect the site through engaging with the government, and the various legal actions, a walk to protect the site entitled ‘It IS Sacred’ was held in June of 2016 led by Algonquin grandmothers and elders. The walk started on Victoria Island and went up Booth Street, then to Wellington St and on to Parliament Hill (see video). It was also that morning that Romeo Saganash spoke in Parliament about protecting the sacred site.

Similar walks have been held annually since (see 2018 video) but with less participants. There is one being planned this year for September 20 (details TBA).

Other actions have been held as well:

- An event that included the planting of a tree of peace on Victoria Island (June 2015)

- Opposition to Arboretum music festival choice of Zibi as venue, leads to panel of Algonquin speakers on the issue (video p1 & p2) but with only one panelist opposing the development (August 2015)

- Counter-action (article / video) at the first Ottawa open-house for condo sales (November 2015)

- Protests and petitioning of local Liberal MP / Environment Minister Catherine McKenna, led by Stop Windmill, another group formed to protect the Sacred Site (Summer 2016; see July article / video).

- Various:

*Public educational events, including:

November 2015 with Evelyn Commanda, Douglas Cardinal, and John Ralston Saul, and

December 2015 with 11 speakers and musical performers;

*Petitioning (the largest has 8,200 names, and over 1,000 on the official Parliamentary petition);

*Fundraising, info-tabling, articles, videos, podcasts, and more…

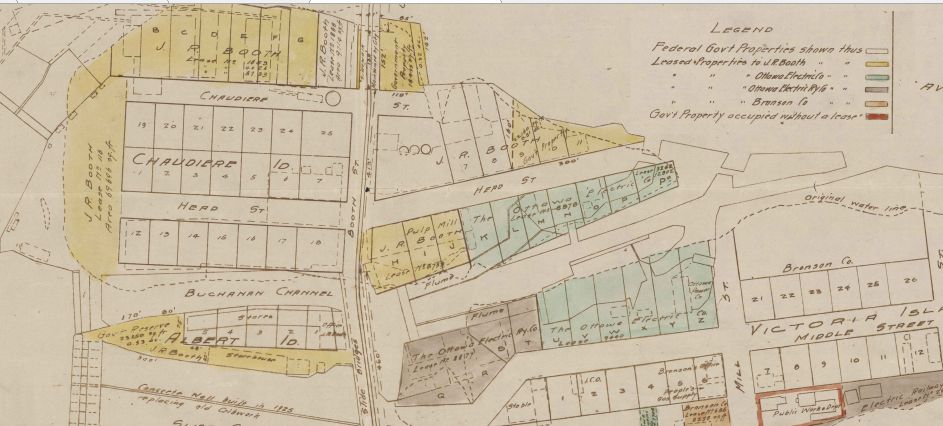

The issue of land ownership at the site is still of contention, even apart from Aboriginal title. The overall claims to ownership of the land by Windmill et al, by way of Domtar and the government, is challenged in detail by historian Lindsay Lambert. According to Lambert, lands on the islands were either leased or licensed to private interests (lumber companies and hydro) by the government – but were held as crown (government) land and not fee simple (private) ownership: “The only reference in the Land Registry to anything being in “Fee Simple” dates from 1960. In that year, the City of Ottawa decommissioned most of the public streets, Chaudiere Street, Head Street and Union Square on Chaudiere Island, and transferred them to E.B. Eddy Forest Products” [EB Eddy was later acquired by Domtar]. The pre-computer land registry records for the islands are compiled here (as micro-filmed in 1998).

Lambert has also made available a 1926 government map that seems to display all island lands as held by the government (see embedded image below), and it is unclear if or at what point the government transferred any other ownership (other than the December 2017 Order In Council for the non-Domtar 1/3 of the island lands slotted for development). Lambert also claims that it was and still is illegal for the government to do so, based on a pre-confederation Order-In-Council still in effect that designates the land at the falls only for public purposes (which both logging and hydro were considered to be) – and that the designation can only be changed by an act of Parliament.

* Lambert’s detailed explanation is included in this letter to an NCC employee in May 2018, as well as this letter to the Governor General in January 2019.

See PDF for full version.

ALGONQUIN LAND CLAIM FOR EASTERN ONTARIO:

Since the early 1990s the federal and provincial governments have been negotiating with the Pikwakanagan First Nation about a large area of land in Eastern Ontario that includes Ottawa. In the 2000s, nine non-status communities were brought into the negotiations, forming the Algonquins of Ontario (AOO) corporation with Pikwakanagan. AOO decision-making is based on 16 votes: nine votes are from the single ‘Algonquin Negotiation Representative’ (ANR) of each of the nine non-status communities, and the other seven votes are from the Pikwakanagan chief and six councillors.

A draft proposed agreement-in-principal (AIP) was gradually developed with main points of the Algonquins keeping 1.3% of the land, and approximately $300 million. In late winter 2016, a non-binding referendum was held on the AIP: it was overall 88% in favour (including 96% of non-status members, but with 56% opposed amongst Pikwakanagan members). Despite the will of the Pikwakanagan voters, Pikwakanagan and AOO leadership held a signing ceremony with the governments in the fall of 2016. It is still a tentative agreement so there are still years of negotiation process to come.

The two pieces included in the handout on the land claim, for background, are:

- Heather Majaury’s 2015 letter to AOO with her reasons for voting No to the AIP

- 2015 interview with Russ Diabo about the land claim (audio with transcript)

For more background on particular issues, see:

- Quebec Algonquins question Ontario land claim 2013 CBC

The land is not exclusively the traditional territory of Algonquins currently based in Ontario.

Also see: Statement of Assertion of Aboriginal Title and Rights 2013 press release. - First Nations finance their own demise through land claims process 2015

Focus on debt imposed via negotiations. By Lynn Gehl and Heather Majaury.

Gehl also has a book The Truth That Wampum Tells based on her PhD on the land claim. - How ‘Algonquin’ are AOO members? 2016 Review of AOO Voter’s List

Summary on pages 1-3. By Peter Di Gangi & Alison McBride, Algonquin Nation Secretariat. - General information on the ‘Termination Tables’ government land claims policy via Idle No More

Also see: 2014 presentation from four Algonquin communities on the federal policies.

And: Chief Harry St. Denis’ testimony to Parliamentary committee, in the section further below. - Chronological listing of E.Ontario Algonquin land claim news, hosted by FOCA cottagers’ association

The majority vote of Pikwakanagan members in the referendum against the AIP is part of the basis of the court case by the Pikwakanagan grandmothers against the Chief and Council and federal government.

This land claim process is a major factor leading to Pikwakanagan and the AOO, already negotiating to cede land title and rights that includes the Sacred Site, being favourable to supporting the development.

It can be confusing in the media when they mention ‘ten Algonquin communities’ referring to the status Algonquin community of Pikwakanagan with the nine non-status communities in Ontario that are not recognized in the Indian Act, versus the ten Algonquin communities (Pikwakanagan and the nine based in Quebec – read Appendix F here) that are the federally-recognized Algonquin Nation.

* Note: “Three other [status] First Nations in Ontario [not part of the land claim] are at least partly of Algonquin descent, connected by kinship: Temagami, Wahgoshig, and Matachewan.” (source)

HYDRO DAM AND PUBLIC PARK:

The original ring dam at the waterfalls was built between 1908-1910.

As the current planned condominium/commerce development was in the works, Hydro Ottawa (with their subsidiary, Energy Ottawa) was working on a new electrical generation facility at the dam.

This additional construction was also opposed by the nine Algonquin chiefs in the AFN-QL and AFN resolutions, but their opposition was much less publicized, and no accommodation or halt was made. It was again the Algonquins of Ontario, including Pikwakanagan, that worked with Hydro Ottawa to provide consent and support for the project (including in the media).

The construction on the upgraded dam involved a lot of destruction of the natural stone at the site .

The hydro company has worked closely with the developers, including for the parts of the island not planned for development to become public parks and access to the falls area.

Douglas Cardinal had worked with Hydro Ottawa consulting with the Algonquins of Ontario to create designs for the park (see pages 23+), but later withdrew his work.

The park adjacent to the falls opened to the public in October 2017 as part of the (controversial) Miwate sound and light exhibit for Canada 150, and then in spring 2018 as a generally-accessible venue – and with tours of the hydro facility available on special occasions or when booked as an organizational tour.

ADVOCACY OF CHIEF HARRY ST. DENIS, AND TRIBUTE:

Wolf Lake Chief Harry St. Denis passed away suddenly and unexpectedly in November 2018.

He had been Chief of Wolf Lake for three decades. See a collection of tributes, and some media pieces, compiled at this post. Also the 76-min new documentary film in tribute, based on an interview recorded with Chief St. Denis, embedded at bottom below.

He had brought together the nine ‘Quebec-based’ Algonquin chiefs to work to protect the site from the developments, initiating the resolutions at the November 2015 AFN-QL (having first ensured it was supported by all nine) and at the December 2015 AFN resolution (which was amended to include in the wording, the name of each community).

In the following two short audios, he describes some aspects of the series of meetings the NCC began to host on a quarterly or so basis (he is also quoted by CBC about these meetings when they were first starting). The cooperation between chiefs ensured the government started to take some responsibility for organizing discussions and also ensured the government included all ten status Algonquin communities at the table – these meetings were likely part of what brought about the first united gathering of the Algonquin Nation in three decades, that he didn’t live to see, this past February (see article in French; bilingual press release). In these audios he also discusses the lack of actual consultation or accommodation in the process, and the second audio includes how the scale of information provided and the detailed contextual work needed for such a process was beyond the capacities of the small Algonquin communities.

LISTEN: These two segments with St. Denis (files: p1 + p2) were excerpted specifically to broadcast by megaphone at the walking tour, from an until-now unpublished Spring 2018 phone interview.

You can read an opinion piece he authored in the Ottawa Citizen in August 2016 about the Sacred Site.

LISTEN: Chief St. Denis was also interviewed in February 2016 on CKCU 93.1FM campus/community radio, by host Chris White alongside Free The Falls group member Peter Stockdale (17-min audio file):

A third audio, the audio from the short video below, was also included as part of the walk.

The video is a Twitter-length (2m20s) selection of highlights from audio of his testimony re: land claims policy at a Parliamentary INAN committee hearing, with accompanying visuals added to create a video format. He does discuss the Sacred Site as well as/ in relation to overall land claims.

(His full testimony, 29-minutes in audio and also text transcription, is included at this link)

* On May 31, the day after this guide was published online, the Chief Harry St. Denis Scholarship for Indigenous Environmental Students was announced, established by Margaret Atwood (neighbour of the St. Denis family on Lake Kipawa) and Indspire. See the press release, and also the official award webpage where contributions can be made.

FILM TRUBUTE: This 76-minute documentary tribute video, “Chez nous à Wolf Lake,” published December 2018, is from a wide-ranging interview with Chief Harry St. Denis conducted by Émilie Jacques for La Télévision Communautaire du Témiscamingue (www.temis.tv). It is almost all in English.

“Émilie discovers the community of Wolf Lake in the company of their late chief, Harry St-Denis. Come and meet a chief who was dedicated to his community through an interview held at the Algonquin Canoe Company, in which you will learn more about the history of this unique community on the territory.”

Interdependent media & in-person learning opportunities for those who are inspired to be part of movements for social justice.

Interdependent media & in-person learning opportunities for those who are inspired to be part of movements for social justice.

Chi miigwetch Greg Macdougall for this great collection of very important work!! This is a thorough outline of the challenges and status of the sacred site at the Chaudiere Falls. So many people believe in it… so many are trying to set things right. Only greed and stubbornness stand in the way. Your article prompted me to re-read the “FINAL REPORT: ALGONQUIN ELDERS’ GATHERING TO DEVELOP A VISION FOR VICTORIA ISLAND March 27 – 28, 2002 Chateau Logue, Maniwaki, Quebec”. This is a report that Zibi took from Grandfather William’s Asinabka website and extrapolated to suit their own purposes. It is important to note that this report was not written by William Commanda. It was compiled by other resources assisting the group. It’s not that it is not accurate, it’s that it is an incomplete complete picture because it doesnt mention ALL the reasons why the Chaudiere/Victoria site was the focal point… WHY Victoria Island was named, and especially WHY it was the ONLY spot potentially available for development AT THE TIME Grandfather and the others were gathering to discuss this. You have to consider that the People have been meeting on those islands for thousands of years. It was indeed a very sacred place. But the islands were not named “Chaudiere, Victoria, Albert” until very recent history. You can’t separate one from the other that way. It was the islands… especially Chaudiere being the ONLY one with a view of the falls! It’s just common sense! It was only a few decades ago that the people were able to start gathering there legally again and the only place available to do that was Victoria Island because Chaudiere Island was COMPLETELY blocked off and under lock and key. It’s been so long that many of the People themselves forgot this place and what it stood for and how very special it was. But Grandfather William knew and he unified the Algonquin nation around this vision, believing that the reclamation and restoration of this particular sacred site was very important. It is now more so now than ever. Its not too late to rally behind it. If you really listen and look closely, it’s not hard to see its potential as key to lighting the 8th fire, its potential for unifying all the Indigenous of Turtle Island, and its potential for reconciling with our Mother Earth. The Great Mystery made Grandfather William a carrier of the 7 Fires Prophecy belt. These are synchronicities we can’t ignore. The ember of his vision still burns. It’s time to add more wood to the fire. Aho!!